Ken Cross

Ken Cross Research Fund

The Ken Cross Research Fund was created in 2011 to recognize the importance of research to the work of bicycle and pedestrian professionals. Ken Cross brought bicycle safety out of the Dark Ages with his landmark 1977 report, A Study of Bicycle/Motor-Vehicle Accidents: Identification of Problem Types and Countermeasure Approaches. Before this study, the field consisted mostly of victim-blaming and "Don’t Dos” created by people who knew little about bicycling safety, crashes, or the benefits of bicycling.

Ken's wife, Joyce, endowed the fund in Ken's honor after his death in 2008. The Ken Cross Fund supports APBP's Student Research Poster Contest, which is held in conjunction with the APBP Conference. Finalists receive registration to attend the APBP Conference, where they compete for the grand prize (registration and travel to attend the next APBP Conference or Walk/Bike/Places, whichever comes next).

Click here to donate to the Ken Cross Research Fund.

Remembering Ken Cross (1934 - 2008)

Ken's friends and colleagues reflect here on the impact of his work and his life.

Katie Moran:

When I was a Highway Safety Management Specialist at NHTSA in the Pedestrian/Cyclist Branch back in the mid 70’s the people who were doing the seminal work on accident typing were like gods. They were the first to provide solid information on why pedestrians and bicyclists were getting killed, and more importantly, what actions could be taken to avoid these crashes in the first place. Ken Cross was one of those gods and I was very nervous about meeting him. He had agreed to preview the results of his landmark work: A Study of Bicycle/Motor Vehicle Accidents: Identification of Problem Types and Countermeasure Approaches at Bike-Ed ‘77, the first national conference on bicycle safety issues.

The conference was held six months before his report’s final publication and attendees were the first to hear his results. He was very nervous about how his work would be received by what he considered the "movers and shakers” in bicycling. I think he expectd people to challenge his methods and argue with his findings - instead they gave him a standing ovation. We all had been hungry for solid guidance on what the most dangerous things bicyclists and motorists were doing, so that we could focus our very limited resources on actions that would have the biggest impact. Ken gave us the clues for solving the mystery. I, of course, became even more intimidated about meeting Ken. I can only say that he was one of the kindest, gentlest, most self-effacing (and brilliant) people I have ever met.

Richard Blomberg:

Ken Cross was a dear friend and valued colleague. When I try to describe him, the words brilliant, charming, loyal, devoted and courageous immediately come to mind. Ken’s contributions to the human factors profession and, specifically, to bicycle safety are legendary. It was a privilege to work with him and be his friend. His grace and courage were something to admire and may not be known to everyone. Shortly before he passed away at a time when his doctors had given him only a few months to live, Ken sent me the following in an e-mail: "I want to thank you for your friendship over the years. It is amazing to me that a New York sophisticate maintained a friendship with a midwestern hayseed like me. Thank Susan for her many kindnesses and tell the kids that I am very proud of them.”

That was Ken. Even when facing his own mortality, he was thanking me for a friendship from which my family and I benefitted profoundly. When I forwarded Ken’s farewell to my son, his response was: "Please tell him how warm our memories of him are and always will be and that we will never forget how wonderful he was to us growing up. Such a great guy. No more need be said except that we miss him terribly and will always honor his memory.”

Bill Wilkinson:

I first met Ken Cross at the Bike-Ed ‘77 conference in the Spring of 1977. His Bicycle Crash study had recently been completed and he was a featured speaker at the meeting.  As I recall, Ken came up to the lectern, said a few words, and froze. Later, he said he’d never addressed such a large audience (i.e., 200 people) before. Ken was a quiet guy! Three things have always impressed me about his Bicycle Crash study. First, the writing was clear and crisp; it was a model of what scientific writing should be. Second, the typology of crash types was very sound, solid, and complete. (My favorite crash type was #36: Weird.) Finally, right from the time of publication, the study was viewed and used as a foundation piece of research: it informed and influenced everything that followed related to bicycle safety education and training. As I recall, Ken came up to the lectern, said a few words, and froze. Later, he said he’d never addressed such a large audience (i.e., 200 people) before. Ken was a quiet guy! Three things have always impressed me about his Bicycle Crash study. First, the writing was clear and crisp; it was a model of what scientific writing should be. Second, the typology of crash types was very sound, solid, and complete. (My favorite crash type was #36: Weird.) Finally, right from the time of publication, the study was viewed and used as a foundation piece of research: it informed and influenced everything that followed related to bicycle safety education and training.

On a lighter note, I enjoyed visiting Ken and his family, both in Santa Barbara and later down at Ft. Rucker, Alabama. I vaguely recall the all-night poker game with three Ph.D research psychologists (now there is a challenging group to bluff!) and I vividly recall, then and always, Ken’s wonderful, warm home and family. Ken Cross was a class act.

Roger DiBrito:

Before Bike-Ed ‘77, most bike education programs consisted of a list of don’ts and a few coloring pages. Materials were designed to please motorist; the message: "Stay out of our way.” Ken opened the doors of empowerment. From his talks and writings it was clear to me that we are called to teach children to avoid car crashes with knowledge and skill not submission and fear. Before Bike-Ed ‘77, most bike education programs consisted of a list of don’ts and a few coloring pages. Materials were designed to please motorist; the message: "Stay out of our way.” Ken opened the doors of empowerment. From his talks and writings it was clear to me that we are called to teach children to avoid car crashes with knowledge and skill not submission and fear.

Ken developed a Crash Countermeasure program and introduced it as a Bicycle Education Program to the Santa Barbara school district. This program stepped away from the coloring pages and addressed road hazards, lane position and driver behaviors head on. Diagrams are sophisticated and effective. Video images are precise and prescriptive. Ken helped many of us (including myself) to understand crash causation factors and how to reduce risk and unintentional injury.

We were honored by his presence at Bike-Ed ‘87, held in Missoula, Montana. All effective pedestrian/bicycle education programs are based on Ken’s work. Yes, many others, Dr. Don La Fond, Rich Blomberg, Dan Burden, John Williams, and the father of Effective Cycling; John Forester played important roles, but I believe all would agree Ken’s work is the foundation of the education effort. Today, effective programs use images modeling proper behavior, on-bike activities to build riding skills, and in-street lessons practicing turns, holding lane position and predictable riding. Instructors must understand Ken’s work and identify how to reduce risk. See the evolution of Ken’s work in Montana on Facebook: Journeys From Home Montana. John Forester played important roles, but I believe all would agree Ken’s work is the foundation of the education effort. Today, effective programs use images modeling proper behavior, on-bike activities to build riding skills, and in-street lessons practicing turns, holding lane position and predictable riding. Instructors must understand Ken’s work and identify how to reduce risk. See the evolution of Ken’s work in Montana on Facebook: Journeys From Home Montana.

Dan Burden:

It was in the early years of modern bicycling (mid-seventies) when Dr. Kenneth Cross (Ken), puzzled over how and why children and adults were being injured or killed on bicycles. Ken took his disciplined and proven human factors science - a science that made him one of the best people in the world to prepare combat and commercial pilots to keep planes in the air - and he applied it to everyday people trying to balance on two wheels and mix with motorized traffic.

Ken chose not to do this alone. And we were the lucky ones he called upon for expertise and understanding of what he was up against. We were like kids holding the lens for the scientist. Yet Ken had a way of reversing that, referring to himself as the hayseed. Something he believed, but I know was not the case. Ken untangled a mystery and enlightened about everything we do today - riding, teaching, talking to reporters, planning, designing cycle tracks and promoting active transportation.

There had to be a Ken; he was an icon and a beacon. He put science behind the sport and transport we cherish. Ken took a chaotic mass of senseless data and useless victim (or driver) blaming and made sense out of what can go wrong. He turned complex and "uncontrollable” events into understandable and avoidable human failings. Ken gave us the ability to develop countermeasures, allowing us to teach others to prevent needless trauma. For this reason, we honor Ken Cross.

Who was Ken Cross?

Ken was born on the 4th of July, 1934 in Osage County, Oklahoma, in a house just shy of the Kansas state line. He grew up in Wichita, Kansas, where his father, Wayne Cross, owned a grocery store and his mother, Lorraine, ran a dress shop. In high school he competed in the pole vault, had a tap-dancing act, and learned to ride a unicycle.

The first in his family to attend college, Ken earned a Master’s and PhD in Psychology from Kansas State University. After completing his dissertation, he joined the Air Force and worked at the Pentagon, where he developed training materials for the high-security red phone system that presidents use for important calls. (Yes, he got to listen in.) He learned to SCUBA dive in the Pentagon pool.

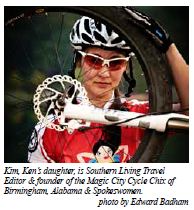

He met his wife, Joyce Cross, an energetic artist with a poker face and a knack for practical jokes, at Anacapa Sciences, the Santa Barbara company where he was later named president. They were married in 1972 and had a daughter, Kim. In 1981 the family moved to Ozark, Ala., where Ken conducted research on flight simulators, grew impressive tomatoes, and took his family waterskiing on a catfish pond near their house in the woods. He built an epic rope swing on a hillside tree and told bedtime stories at sleepovers. People still talk about both.

Ken believed in telling the truth, even when it hurt. He prided himself on his ability to outwork men half his age, though he didn’t rub it in. He had faith in the scientific method, especially for his daughter’s 3rd-grade school projects. He also edited her elementary school papers so ruthlessly that he inspired her to become a writer just so she could edit him. He avoided cursing in front of her by using phrases like "Golly Willikers!” and "Jiminy Christmas!” His best words of advice were "Tough luck, cream puff,” and "Suck it up.” He delivered his most sublime instrument of affection, the fatherly lecture, at the end of a dock on Poquito Bayou.

Ken loved his work. His research paved the way for computer-generated maps and flight simulators. At the Naval Missile Center in Oxnard, California, he worked on the first computer-generated display ever built. He will be remembered for his outstanding leadership at Sikorsky Aircraft, where his crew station design team developed and evaluated new pilot-vehicle interface designs for helmet mounted displays and other advanced-technology systems for the Comanche military aircraft. Ken loved his work. His research paved the way for computer-generated maps and flight simulators. At the Naval Missile Center in Oxnard, California, he worked on the first computer-generated display ever built. He will be remembered for his outstanding leadership at Sikorsky Aircraft, where his crew station design team developed and evaluated new pilot-vehicle interface designs for helmet mounted displays and other advanced-technology systems for the Comanche military aircraft.

He found solace in fishing, though he preferred catching. He would awake at 4 a.m. to unofficially guide friends on fishing trips in the Gulf of Mexico. After setting the hook, he’d hand guests the rod. He insisted on baiting his wife’s hook, even though she knew how. His daughter loved taking him fly fishing in trout streams, but he preferred salt water and bait. "I’m a member of the catch-and-filet club,” he said. His son-in-law knew he’d been approved when Ken let him drive the boat. On their last fishing trip together, just weeks before his death, Ken caught a good-sized trigger fish.

He loved mystery novels, the Bee Gees, martinis, bad puns, and off-color jokes. He sang "Summertime,” swing danced, and cooked a mean chili (secret ingredient: beer). He enjoyed pretending to be annoyed by Tchotchke, a miniature Yorkie who thinks he’s a Rottweiler. But he slept with that dog every night. When his daughter asked him to pen a letter to his infant grandson, he wrote a 12-page children’s story, his first work of fiction. The tale features a bully named Tug McCorckle, a hero named after Ken’s grandson, and a grandpa who gave grandfatherly lectures, including how to throw a punch.

Kenneth Dewayne Cross, 74, died at home on December 10, 2008, 16 months after being diagnosed with cancer.

"I’m quite optimistic about the future of bicycling and bike safety in this country. Since the new bicycle "boom” began there has been significant change in attitudes. I am pleased by the increasing rationality among those concerned with bicycle programs. There is less emotionalism and more informed discussion at bicycle conferences. Definitive data are beginning to appear from bicycle research. Funding agencies at the national level have become aware of bicycle safety and the social benefits of bicycling. All of these changes point to a promising future for bicycling in the United States.”— Ken Cross, 1978

|

Before Bike-Ed ‘77, most bike education programs consisted of a list of don’ts and a few coloring pages. Materials were designed to please motorist; the message: "Stay out of our way.” Ken opened the doors of empowerment. From his talks and writings it was clear to me that we are called to teach children to avoid car crashes with knowledge and skill not submission and fear.

Before Bike-Ed ‘77, most bike education programs consisted of a list of don’ts and a few coloring pages. Materials were designed to please motorist; the message: "Stay out of our way.” Ken opened the doors of empowerment. From his talks and writings it was clear to me that we are called to teach children to avoid car crashes with knowledge and skill not submission and fear. John Forester played important roles, but I believe all would agree Ken’s work is the foundation of the education effort. Today, effective programs use images modeling proper behavior, on-bike activities to build riding skills, and in-street lessons practicing turns, holding lane position and predictable riding. Instructors must understand Ken’s work and identify how to reduce risk. See the evolution of Ken’s work in Montana on Facebook: Journeys From Home Montana.

John Forester played important roles, but I believe all would agree Ken’s work is the foundation of the education effort. Today, effective programs use images modeling proper behavior, on-bike activities to build riding skills, and in-street lessons practicing turns, holding lane position and predictable riding. Instructors must understand Ken’s work and identify how to reduce risk. See the evolution of Ken’s work in Montana on Facebook: Journeys From Home Montana.

Ken loved his work. His research paved the way for computer-generated maps and flight simulators. At the Naval Missile Center in Oxnard, California, he worked on the first computer-generated display ever built. He will be remembered for his outstanding leadership at Sikorsky Aircraft, where his crew station design team developed and evaluated new pilot-vehicle interface designs for helmet mounted displays and other advanced-technology systems for the Comanche military aircraft.

Ken loved his work. His research paved the way for computer-generated maps and flight simulators. At the Naval Missile Center in Oxnard, California, he worked on the first computer-generated display ever built. He will be remembered for his outstanding leadership at Sikorsky Aircraft, where his crew station design team developed and evaluated new pilot-vehicle interface designs for helmet mounted displays and other advanced-technology systems for the Comanche military aircraft.